Working through others is hard; doing it without a map is more challenging. The triadic lens offers a way to focus organizational design on the right social interactions rather than leaving it to chance.

Organizations are designed—but not necessarily by a designer.

“Design is a plan for arranging elements in such a way as best to accomplish a particular purpose.”

—Charles Eames, American designer and architect

The act of design is one of intention. Not every design emerges intentionally, however—self-organizing systems will iterate through designs even without the guidance of a knowledgeable designer.1 The critical difference is whether the components of a system are organizing themselves as guided by well-placed guardrails or something more haphazard.

Will Larson, CTO of Calm, says that leadership is the experience of knowing what ought to be, the awareness to understand what is, and the care to do something about the gap.2 We might then categorize leadership tools in three ways: our tools may help us understand and interpret what reality is, decide what the future should be, or they can help us build the bridge from here to there.

What we create together is a facsimile of the way we communicate.3 For our companies to create what we envision for them, we must build a toolkit that allows us to design better social structures.

Lenses help us see clearly.

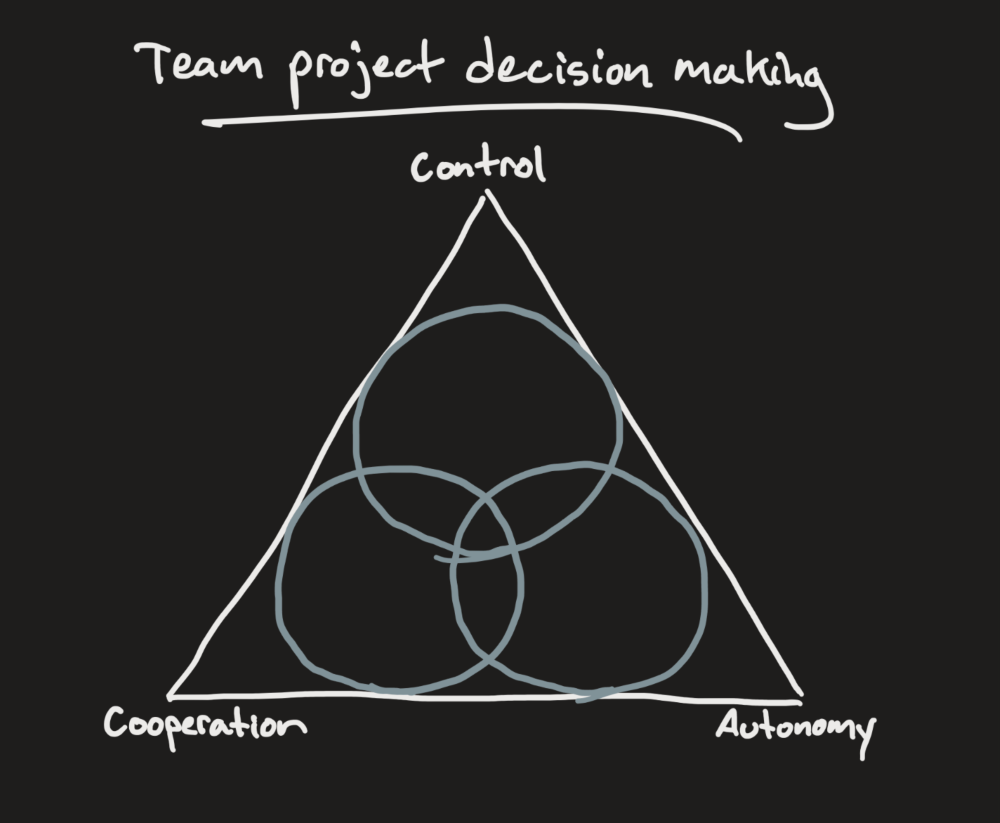

Something I’ve found helpful in thinking about the people systems around me is Robert Keidel’s triadic lens of human interaction. He suggests that humans interact in three distinct ways:4

- Where one has station over another to direct their actions, it may be described as control. (Think of it more akin to “authority” than a synonym for “micromanagement.”)

- People cooperate when they act together without power dynamics compelling them to.

- With social behavior underpinning almost all human psychology,5 autonomy registers as a category of cognizant social interaction, despite the absence of other people.

Control, cooperation, and autonomy form a triangle within which we can plot all levels of human activities from a concrete view of how a particular meeting went to the abstract nature of a firm’s operations.

Try it out: On some paper, copy the following diagram. Think of something in your organization that you wish were going better—maybe a recurring meeting proving ineffective or a pattern of communication breakdown between two departments—and title your diagram after it.

I’ve observed that my team has been making decisions that were missing essential requirements, so I’ll name mine “Team project decision making.”

Let’s dig into each aspect a little deeper.

Control is hierarchical.

Where a system leverages more control, it brings to bear more global context. Activities are centrally coordinated. Coach-oriented games, shareholder-focused companies, steeper organizational structures, highly sequential work procedures, and mandated decisions are all control-dominant.

Autonomy is separate.

Flatter reporting structures yield less oversight. Golf doesn’t entail much teamwork. Subject matter experts have grown their skills in an area. Mass information dissemination relies on individuals interpreting the meaning and putting the content to work. In decision-making, autonomy means sourcing input from various contributors that aren’t coordinating with one another. Local context is found mainly at the individual level.

Cooperation is flat.

Basketball is cooperative. Org structures that lean this way tend to be flatter and more ambiguous. Pay structures that favor cooperation tend toward socialism. Collaborative decision-making builds consensus but also takes longer. Less about the global or local contexts, cooperation is how context moves, both vertically and horizontally.

It’s all a fractal.

As you zoom into any area, even a place focused on one of the variables, the same tradeoffs reemerge. Meetings are mainly cooperative (in contrast to other organizational systems such as rewards (autonomy) or decisions (control)). When breaking down the concept of meetings, we again find different focal points: a forum, where individuals represent different viewpoints, is autonomy-focused; decision-making meetings are for a group to exercise its authority, which is a control activity; and team building meetings increase the cooperability of the team.

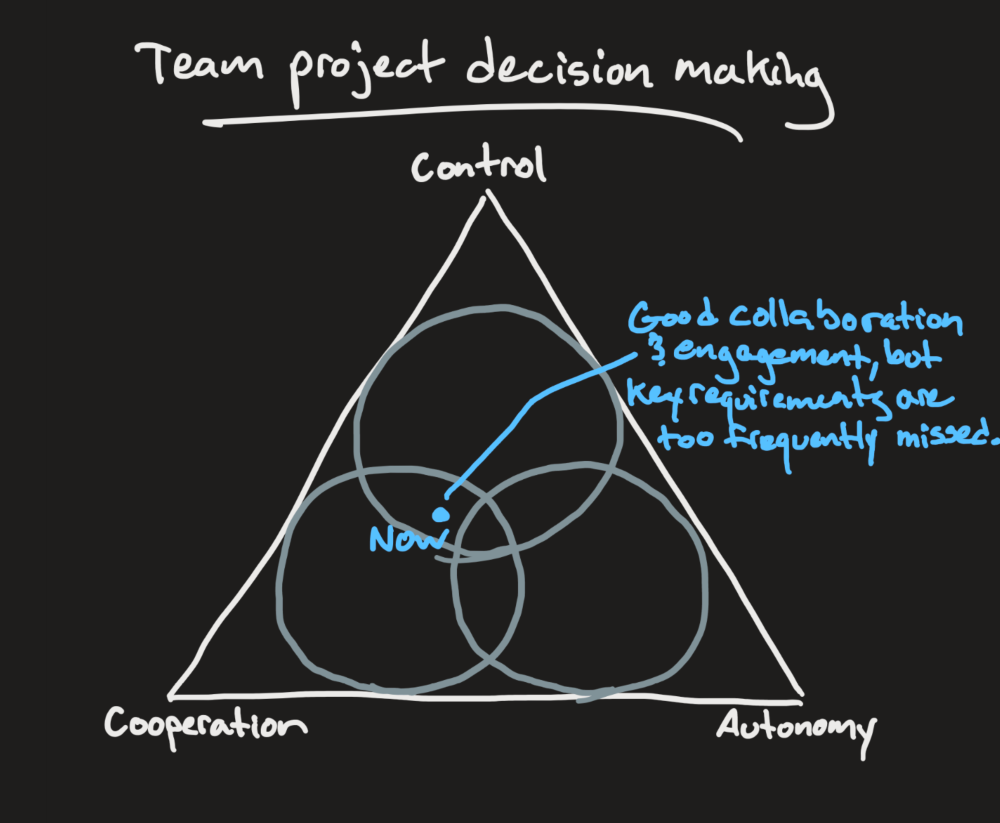

Try it out: Consider the area you’ve identified needing improvement. Which traits does the situation currently embody the most? Or conversely, which characteristics do you wish it expressed more strongly than it does? Place a dot in the diagram once you decide where it fits best. You Are Here.

I see that my team works together effectively to make decisions, and individuals are highly engaged in the process. Decisions are well-made but miss some details. I’ll place my dot halfway between Control and Cooperation, outside the center of the diagram. There’s a healthy amount of autonomy in their approach, but it’s not the dominant trait.

Leaders design the future.

Keidel’s framework comes with two warnings and one core purpose.

It exists to help you clarify what you want. But you must work to understand the complexity of your system enough to avoid an overly simplified caricature, and you must be decisive about what truly matters in it.

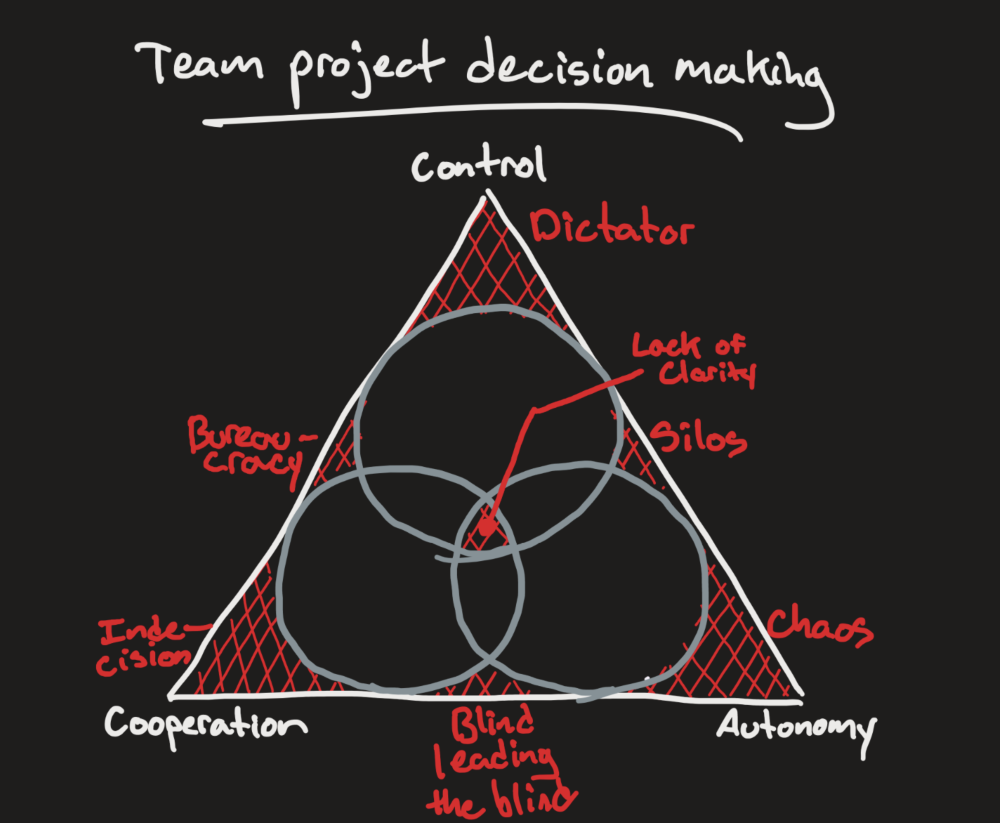

Analysis 1: Each variable counts.

One-variable designs problematically overemphasize a trait. Where we may healthily focus on one variable with the support of the other two, it becomes pathological when the other two are not at all involved.

Conversely, a two-variable design will entirely diminish the potential of the excluded variable. It takes all three to work.

Analysis 2: Design means prioritizing.

But not all three without differentiation! Like in all other prioritization, valuing everything is valuing nothing. Undifferentiated design offers us a confused system where the lack of strategic tradeoffs compounds difficult decisions. This makes it hard to predict which system aspect will ultimately win in a particular situation, preventing smooth operation.

Try it out: Reference the diagram above. Does your dot sit in any of the seven problem zones? If so, does your problem match these downsides, or is the current system making tradeoffs that you haven’t yet considered? Update your starting point if needed.

Analysis 3: Intention is everything.

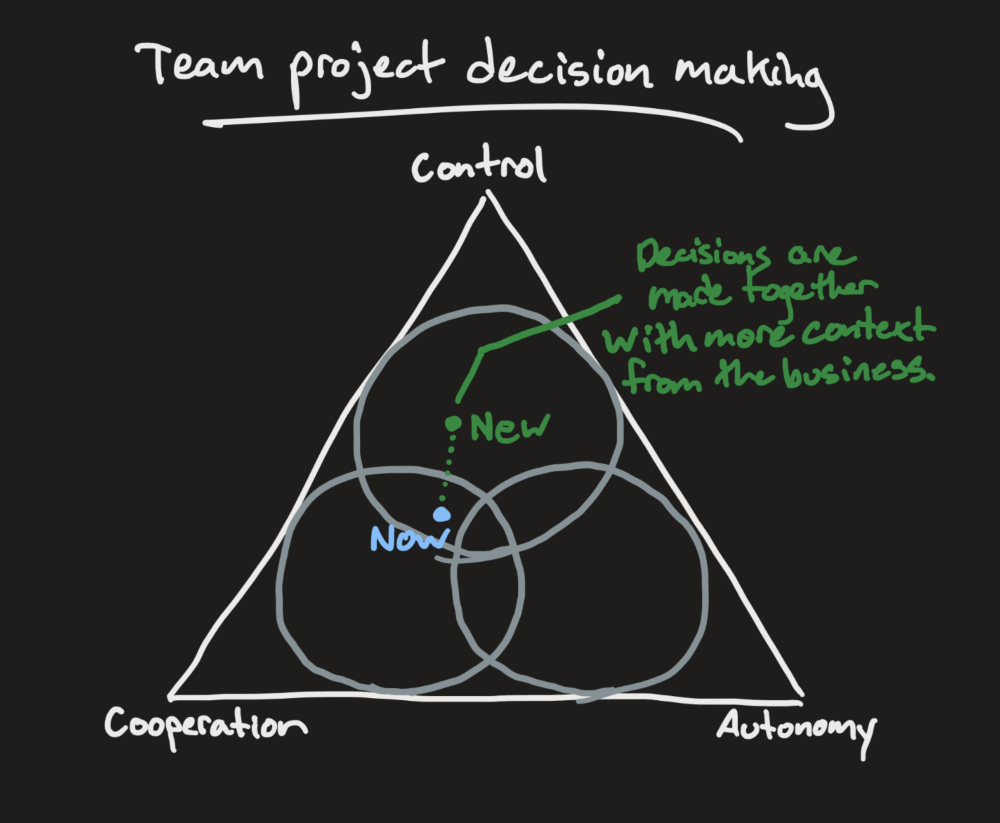

The problem zones are only one signal. The real utility is in thinking deeply about what tradeoffs you need to be making and where that might end up on the map. This is the hard part, and unfortunately, the framework does not ship with serving suggestions.

The model takes our attention off the most obvious solutions to allow us to think more broadly about what we’re trying to create. Where it might be obvious that I need to add more structure to my team’s decision-making process, it wouldn’t otherwise have been evident that this is only a symptom; that there are more parts of their work needing approval mechanisms, and we have more opportunities to layer in global context to inform their decisions better.

Try it out: Identify where on your diagram you need to move the situation by evaluating which tradeoffs balance it ideally. Perhaps the obvious solution in your improvement opportunity was to add more accountability, but the higher perspective also illustrates that more top-down context sharing is also necessary.

In my team, I want to convey more of the global context to them, and am otherwise happy with how they’re engaging. I’ll set my destination point a bit higher into Control.

With the destination identified, chart a course by thinking through what changes create that trajectory—beyond directly solving the problem at hand. By identifying the more resounding theme of the issue, you can solve it more thoroughly along multiple vectors and resolve other problems you would not have otherwise noticed as being related.

Leaders use many tools to make corrections within their organizations and teams. In my experience, prescriptive practices like scrum, strategic playbook design6, skip-level one-on-ones, and so on fill most of the toolbox. Some of the tools in the box are more abstract (and powerful), suggesting which levers are available to adjust in a system.7 Rarer still are the tools that reveal which changes are necessary—I like the triadic lens because it falls into this category. Tools in this category are harder to use, but because they challenge our more easily-formed beliefs, they can also drive more robust decisions.

-

↩

Donella H. Meadows and Diana Wright, Thinking in Systems: A Primer (White River Junction, Vt: Chelsea Green Pub, 2008). (notes)

-

↩

Will Larson, “To Lead, You Have to Follow.,” May 25, 2020, https://lethain.com/to-lead-follow/. (notes)

-

↩

Melvin E. Conway, “How Do Committees Invent?,” Datamation, April 1968.

-

↩

Robert W Keidel, Seeing Organizational Patterns: A New Theory and Language of Organizational Design (Washington, D.C.: Beard Books, 2005). (notes)

-

↩

Will Storr, The Status Game: On Social Position and How We Use It, Unabridged (London: William Collins, 2021). (notes)

-

↩

Patrick Lencioni, The Advantage: Why Organizational Health Trumps Everything Else in Business, 1st ed (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2012). (notes)

-

↩

Gary Neilson, Jaime Estupiñán, and Bhushan Sethi, “10 Principles of Organization Design,” strategy+business, 2015, https://www.strategy-business.com/article/00318?gko=31dee. (notes)